Fashioned from the earth, we are souls in clay form.

— John O’Donohue, Anam Cara

In this article, I will explore the history of material and how ceramics and pottery evolved and its contemporary uses through the lens of both industry and craft-making practices.

In its primary form, clay is a mixture of mineral substances, notably magnesia, alumina, silica and water. Clay has a high degree of plasticity, thus easily creating any shape or form. Clay’s malleability permitted new inventions to take place, such as writing, as clay tablets were the first writing surfaces, upon which people inscribed text in the age of Mesopotamia in 3,300 BCE. It is such an antediluvian, durable and ubiquitous material, as we use it to produce shingled roofs (rendered from terracotta or red clay, that comprise most houses on the coast of Southern Mediterranean). Moreover, floors are clad in tiles in Mediterranean, Arabic and all warm climes to ensure coolness of the space. During the eighteenth-nineteenth century, the excavations of ancient Roman villas after the eruption of Vesuvius volcano, and upon discovery of intact tiles, mosaics and various amphorae in Herculaneum and Pompeii proved that mosaics rendered from clay is an incredibly durable material that withstands both lava and time, not only have their tiles remained intact, but also the colours and designs remained as vibrant as ever.

I have a personal affinity to ceramics: my father has been a manufacturer of ceramic tiles for twenty years. During this time, I have had the privilege of working in this enterprise, Golden Tile, in various capacities, including designing tiles, managing factory’s social media, helping out at children’s events (yes, that too), and shadowing him on monthly meetings (among the executive positions, more than fifty percent are occupied by women — had to brag). I have first-hand witnessed how the raw material is mined from the quarries, pulverized in cage mills, baked in a kiln, cut at a ninety-degree angle (very important process in the tiling world), glazed and packaged. Phew.

The process of creating a ceramic tile is thus: all the ingredients pass through an ‘arc’, after which the formed shapes known as ‘clay tablets’ are put through a press with nylon filter cloths. Afterwards, water is drained through the mesh, rendering the texture of clay tablets as soft and malleable, like plasticine. The forms are subsequently placed into kilns, and after being ‘cooked’ at the high temperature of 1,750 degrees Celsius, and emerge as clay biscuits. Quite literally, hot off the press.

I was privileged to visit some of the renowned ceramic trade fairs in Europe, including Cersaie Bologna Fair, as well as Cevisama in Valencia. Since then, I understood that ceramics is a world of its own. The more I researched, the more I understood how ancient the material is and how much it surrounds us in our daily life.

Ceramics became the signifier of cultural heritage for many nations, including United Kingdom, Denmark, Ukraine, among others.

The British potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood’s legacy is one such example.

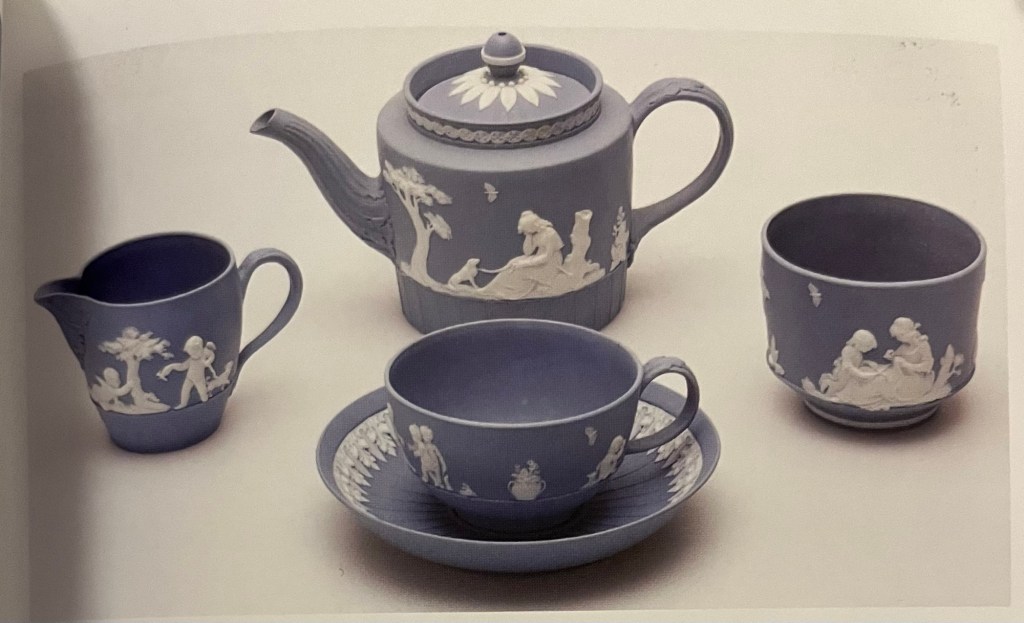

‘Night Shedding of Poppies’ or ‘Venus and Cupid’ motif.

The English potter Josiah Wedgwood invented the jasper material (or clay stoneware) in 1777 that had a lasting impact on the decorative arts not only in England, but Europe, too. Its matte or ‘biscuit’ finish became the signature quality of its stoneware. The body of the material itself was quite coarse that lend itself to durability, but coated with an ultra-thin layer of of clay that gave it its ultra-polished look. Today it is known as a type of porcelain due to its smooth quality.

Wedgwood married the ancient craft of pottery to the industrial manufacturing process that permitted mass-production of cameo portraits and re-popularized classical genre in arts. Jasperware and the Queensware became a native invention of England and affixed the cultural legacy with Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire (Wedgwood has also financed building of a bridge that linked the ancient town to industrial centers, such as Liverpool).

The ‘Queensware’ (as the enterprise was supported by Queen Charlotte), should not be confused with Jasperware (his later invention): the former is cream-bodied earthenware that became imitated among Continental nations during the eighteenth century, notably France — their alternative was called ‘faience anglaise’ (English ceramic ware).

The unique feature of jasperware (patented in 1777) was its matte finish that permitted bright and vivid reproduction of colour. Contrary to the typical material used for tableware, porcelain, this material was coarser, yet maintained a polished look. The distinction between china and earthenware is the composition: china comprises fifty percent of bone, and the remainder is stone and clay that yields the fragile appearance; while earthenware contains ground flint, ball clay china and stone that, in turn, gives the form more durability.

However, jasperware managed to achieve both: a sleek look combined with a durable and sturdy body. It took Josiah Wedgwood more than thousands experiments to come up with a distinct recipe, yet once it has been figured out (and closely-guarded), the product variety was potentially limitless: from table- and tea-ware; vases, pots, to fashionable at the time cameo portraits, fireplace plaques, among others.

Wedgewood pottery stands out due to its remarkably vivid colours: lapis lazuli blue, sage green and crimson, colours that all evoke nobility.

As the lead technologist of the Golden Tile enterprise, Yana Pokroyeva, shared with me, each colour requires a specific recipe and variance. Surprisingly, what would constitute the most expensive colour in oil painting (historically, ultramarine blue due to its far-flung deposits, notably Afghanistan), in ceramic production, surprisingly, would be red, due to cadmium oxide or a mineral that occurs more naturally, monteponite. It is even more difficult to obtain than a cobalt one, rendering red a more expensive pigment in production than blue. Thus, geology and chemistry truly drives the design in ceramics.

The Wedgwood enterprise proved crucial in popularising the classical genre by including motifs largely derived from the Ancient Greek mythology. During the eighteenth century and the hey-day of the Grand Tour, these items were particularly in favour. However, Wedgwood’s achievement did not stop solely at creating fashionable ceramic items. As an abolitionist, he manufactured medallions, depicting a black man with an engraved saying, ‘am I not a man and a brother?’, creating the first ever circular pin mentioning a political statement — I Voted’ and anti-nuclear-themed ones, to name a few. Thus, the Wedgwood Pottery helped to propel ceramic production from craft into the new industrial arena.

However, Stoke-on-Trent was already associated with ceramics, or as it was known ‘The Potteries’. The name derives from the geographical positioning of the two villages — on clay and coal reserves.

Established in 1793 by Thomas Minton, the factory quickly became known for its dinnerware and materials, notably Parian porcelain, majolica (lead glazed covered earthenware) and bone china. However, from mid- nineteenth century, his successor Herbert Minton inaugurated a new stage in their production: tile making. Named Minton, Hollins and Company, as the enterprise became later known, revived the encaustic tile method popular in the Medieaval period in England. It includes impressing a design carved on a wooden mould onto a pre-fired clay tablet.

The Mintons of Staffordshire are also an important venture in affixing the ceramic capital in England. Mintons’ impressive portfolio includes tiling floors of buildings associated with centers of the free democratic world: Houses of Parliament and U.S. Capitol. Another exceptionally notable landmark is York’s Minster Cathedral, in particular the Chapel (by the way if you haven’t been, it features the most spectacular display of stained glass windows!). During the nineteenth century (1844-45), with Sydney Smirke at the helm of the operation, Mintons tiled the York Mister’s Chapel with four unique designs (featured in images below). Mintons were part of the nationwide Revivalist Movement that looked back to Middle Ages for inspiration, especially for the Gothic style in architecture and other craft techniques (Augustus W. N. Pugin and Sir Charles Barry was a major figure in this movement to whom we owe the current look of the House of Parliament).

Part of the larger Prior colours could be inlaid within one tile, akin to a puzzle, by way of forming a pattern on the mould and the resulting depressions are filled with multicolored slip clay. This creates a pattern that remains intact even when the rest of body’s tile is worn down. The original yellow over glaze of the tiling on York Minster’s floor is still visible on the tiling.2

Compared to other materials, such as marble, encaustic manufacturing method stands out in both durability and design. Over the decades, the tiles showed little signs of wear.

Denmark was also another monarchy whose ceramic production is synonymous with their nation’s heritage — Royal Copenhagen. The Royal Porcelain Factory was founded in 1775 by Frantz Heinrich Müller with the aid of a royal charter. Queen Juliane Marie’s interest in minerology, combined with the backdrop of the Age of Enlightenment and scientific progress, propelled the venture into life.

The distinctive cobalt blue pigment (or more accurately, cobalt zinc silicate), was sourced from Norway (known for its cobalt deposits). The backdrop is white bone china that became the signature look for Danish ceramic ware and yielded a multitude of monochromatic designs. During the ‘ceramic boom’ among the aristocracy, such objects became revered and often were utilized as diplomatic tokens among the nobility. Porcelain china became a diplomatic token among royalty and aristocracy. Both Wedgwood’s Jasperware and porcelain produced by Royal Copenhagen are known as ‘prestige’ wares, highlighting their affiliation with highly-valued objects akin to fine art.

In Ukraine, pottery and ceramic ware have also been part of an ancient tradition since the Tripoli era. Much like England, we also have an entire village called Opishya in the Poltava region dedicated to the pottery craft.

During the war period, ceramic tiles remain as a reminder of our heritage and preservation of culture. Recently, Kyiv’s balbekus Bureau have completed a renovation project that centers around restoring tiles that were damaged during the war. Each donor’s signature was engraved on the verso side of the tile — that way they are eternally inscribed into Ukrainian history and its cultural legacy.

I found that people have a special reverence for ceramic objects. In our household, we had the Old Country Roses tea set featuring burgundy, pink and yellow roses that my mother loves so much (during each visit to London, our must-visit would be to a park or a garden to see and scent marvelous rose bushes). They are one of our most beloved possessions, as I hold fond memories of my mum and dad sipping Oolong and jasmine brews in our old home. Royal Albert China (founded in 1902 that is currently owned by Wedgwood) manufactured this timeless set in 1962, based on the iconic King’s Ransom pattern designed back in 1921. The designer, Harold Holdcroft, took the iconic design and complemented it with the aforementioned roses from the British cottage garden (the original inventors of cottage core trend).

Closer to my current home, dear Fife, ceramic ware also appears as heritage objects, this time from Wemyss Ware manufacturer in Kirkcaldy. Piglets, cockerels, fish and fruit are prominently featured on the Scottish table ware. As one of sellers at one Topping bookstore (practically an institution here in St Andrews), shares with me, Wemyss’ piglet figurines are to this day beloved objects in Scottish households, and often displayed on mantelpieces over a fireplace.

It is this undeniable nostalgic warmth from this inherently cold material that renders it so wonderful: as opposed to tapestries woven from an inherently warm material (that keep as literally warm during winter), these emanate warmth through in a more figurative way — through memories.

by collector George Bellamy

From hinterland towards the coast of East Neuk, we encounter a smaller, yet by no means a less impressive enterprise — Crail Pottery. It is a family-run co-operative, third in its generation located in the eponymous town. This ceramic sanctuary comprises a pottery workshop with in-house kilns, acourtyard, as well as a store located on the mezzanine floor. Featuring terracotta pots, signature stoneware tableware, hand-crafted earthenware, among others, Crail Pottery is a haven for all ceramic aficionados. Moreover, the atmosphere of the courtyard is truly magical: replete with garden pots filled with geranium and pansies, while the score from Lord of the Rings by Howard Shore fills the air. It is a place that is truly worth a visit!

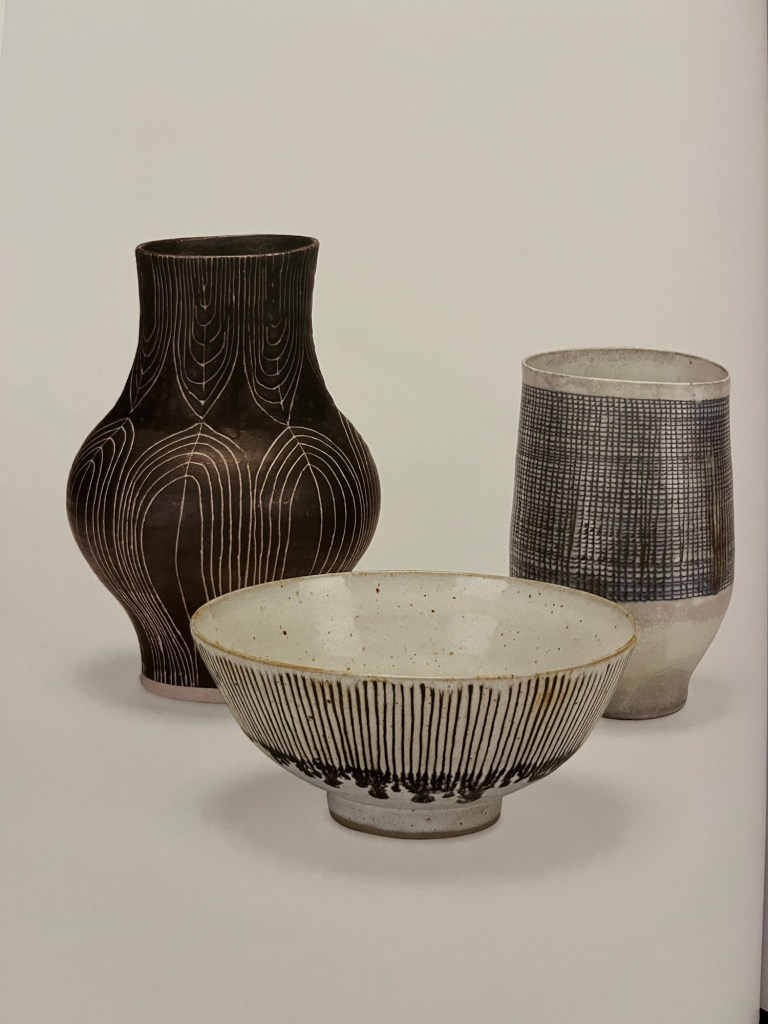

Of course, there are notable individual artisans that give ceramics its gravitas — Lucie Rie to name one. Rie (pronounced, ‘Ree’), was an Austrian emigré, who worked out of her London flat, transforming clay into vessels that had a particular ancient patina. Through age-old techniques, such as ‘sgraffito’ (or cutting out from a material) to the manganese oxide glaze combined with sgraffito etchings, lends the objects a feel of the ancient period, while remaining delicate. Her works are epitome of how each ceramic work is unique in its own right and are a homage to the ancient craft tradition.

An artist whose works exemplify the versatility of clay and ceramics is contemporary Scottish artist and ceramicist Michele Bianco. In her works, the artist is inspired by her native recreates the rugged texture of a mountain rock; thus, her sculptures become miniature versions of the steep and portentous edifications. Some resemble ripples in the sand dunes, others – striations in a vast rock. The transformation from graphic geometric compositions to stand-alone three-dimensions pieces are a marvel for both eyes and hands.

Unlike glass that is a beautiful but rather distant and unattainable material that yields objects that we hold dear, but also fear their imminent demise — a wine glass, a vase or, in rare cases, a chandelier. Ceramics is its opposite — they are containers for symbols of warmth, hearth and joy: a hearty soup, a well-brewed tisane, and, in some cases, keys to our homes.

All of this is written with a hope that we would look at our everyday objects with more appreciation and reverence. In our culture of discarding old objects in favour of new ones, I am glad to see that many cherish their collections, as they become extensions or metonyms for of comfort and love.

All photos are taken from personal archive of the writer and contributers.

Bibliography:

Alan Cuthbertson, ‘History of Wedgwood Jasper’, http://www.collectingwedgwood.com/wedgwood-jasper.

‘Crail Potter’, crailpottery.com.

‘Josiah Wedgwood: Tycoon of Taste’, V&A video.

‘The Antique Floor Company’, http://www.theantiquefloorcompany.org.

‘The Histoy of Wedgewood Jasperware’. https://www.madeinislington.co.uk/history-blog/the-history-of-wedgwood-jasperware-.

‘The Making of Wedgwood Reel 1 1958’, British Pathé, Video, 19:18.

‘The Potteries’, http://www.thepotteries.org.

‘Wedgewood: An Introduction’, vam.ac.uk/articles/wedgwood-an-introduction?.

‘Wedgewood’s ceramic manufacturing archive’, V&A website, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/wedgwoods-ceramic-manufacturing-archive.

Joanne Berry, ‘The Complete Pompeii’, 2013, Thames&Hudson.

George Bellamy, ‘Scottish Wemyss Ware Collection, 1882-1930’, 2019, ACC Art Books.

Andrew Nairne and Eliza Spindel, ‘Lucie Rie: An Adventure of Pottery’, 2023, Kettle’s Yard Gallery.